News & information

Economics

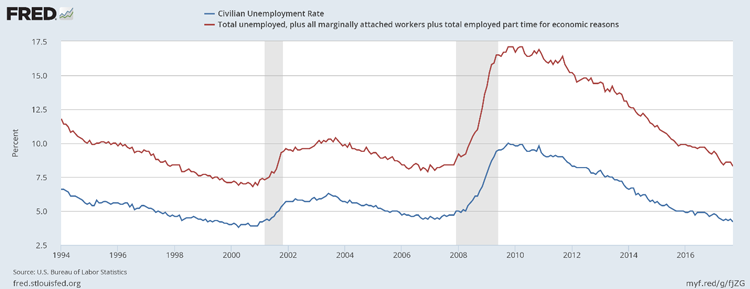

The Bureau of Labor Statistics today released the employment numbers for September 2017. The official unemployment rate (U3) declined to 4.2 percent, a drop of 0.2 percent from August 2017 and 0.7 percent from September 2016. A broader measure of unemployment, U6, fell to 8.3 percent from 8.6 percent in August 2017. Total non-farm payroll employment dropped by 33,000 and is likely the result of Hurricanes Irma and Harvey. Below is a graph of the official employment (U3) and the broader measure of unemployment (U6) from the St. Louis Federal Reserve.

While the official unemployment rate declined, the labor force participation rate stayed constant at 63.1 percent and has remained relatively static over the last year. The number of people who have been unemployed for 27 weeks or longer was essentially unchanged from August and has increased 0.8 percent since September 2016. The number of people who could only find part-time work increased 4.7 percent from 1.633 million to 1.713 million.

The data points to the lingering problem of underemployment in the post-recession landscape. According to a new working paper by Danny Yagan, an economist at the University of California, Berkeley, thousands of people in the hardest-hit areas of the country have struggled to find work and still haven’t found it. Yagan’s research points to an uncomfortable reality that the effects of recessions are lasting longer than in previous decades. This has been confirmed by the Economic Innovation Group’s 2017 Distressed Communities Index, which indicates that cities such as Cleveland and Detroit have experienced essentially no growth since the official end of the recession in June 2009.

The last 15 years have dealt a serious blow to the notion that the effects from recessions are short-term and unemployment quickly bounces back after a downturn. Economic growth remains sluggish, averaging a mere 2.2 percent per year since June 2009—half the rate of recovery after the recession of the early 1980s. There was even a time in the 1960s when economists thought the traditional business cycle had “ended” because recovery from economic downturns was so rapid, with unemployed workers sometimes being rehired by the firms that laid them off. However, the growth of precarious employment in recent decades and the lack of a substantial economic stimulus to address the lack of full employment have meant that unemployed and underemployed workers have fewer options than in previous years. The below graph from the Economic Policy Institute shows how employment recovery in previous recessions were faster and more expansive.